China to lose 51 million people in 10 years

How is China responding to population decline?

Last month, Chinese President Xi Jinping published an article (find it here in Chinese) outlining in more detail than ever before his plan to deal with China’s demographic challenge.

But first, here are five key pieces of information that capture the scale of that challenge and the consequences China is facing:

China is an ultra-low fertility country. China’s Total Fertility rate is estimated to be around 1 child per woman.

China’s population peaked in 2021 and has declined year on year since then.

Over the next 10 years, China is predicted to lose 51 million people from its population. That’s more than the current population of Canada.

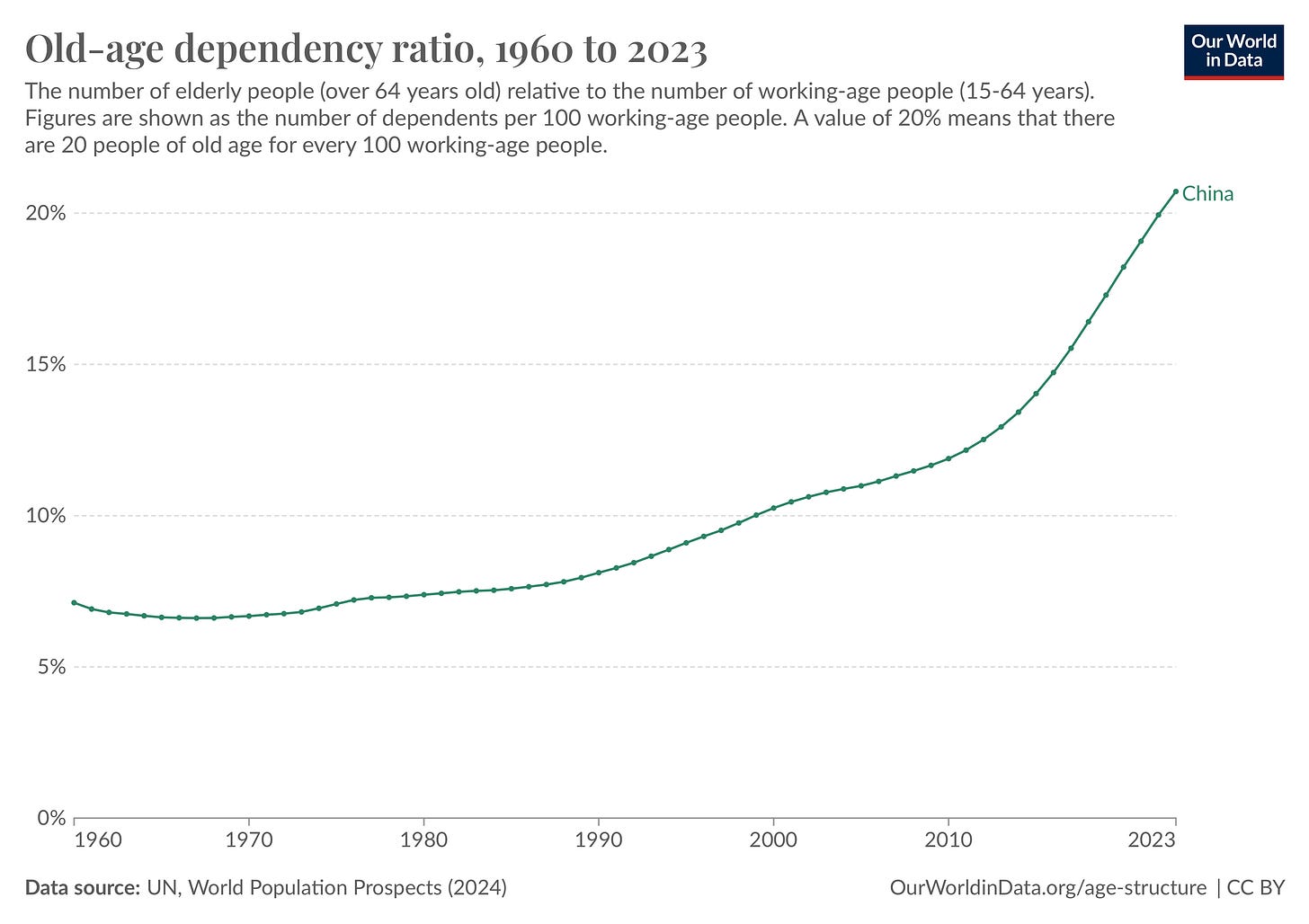

More than a fifth of China’s population is currently aged over 60. The state retirement age is 60 for men, but is rising to 63 in January 2025. For women, the retirement age will increase from 55 to 58 for those in white collar jobs, and from 50 to 55 for those in blue collar jobs.

China’s main state pension fund is forecast to run out of money by 2035. This is primarily due to a decline in the workforce, and this prediction was made in 2019, before the pandemic hit China’s economy.

Even today, with the scale of China’s demographic challenge laid bare, Chinese citizens are not legally free to have as many children as they would like. Instead, when the one-child policy was removed in 2015 after nearly 40 years, it was replaced with a two-child policy. In 2021, that in turn replaced by a three-child policy. As recently as 2020, parents were being fined over $20,000 for having a third child in parts of China.

Important trends that indicate how difficult it might be for China to see its fertility rate increase include increasing youth unemployment and a decline in relationship formation, with a rise in single households. Social scientist Alice Evans has also recently written about viral posts on Chinese social media that are intensely and viscerally negative about becoming a parent, particularly childbirth.

Furthermore, the one-child policy, a cultural preference for sons, and the use of sex-selective abortions (which are illegal in China), have together given China a skewed sex ratio, with 111 baby boys born for every 100 baby girls. The UN Population Fund estimates this means 100,000 female foetuses are being aborted annually.

What’s the plan?

Importantly, Xi’s article explicitly acknowledges the negative effects of low birth rates and an ageing population, including for economic growth. But he also defends the one-child policy and attempts to frame China’s demographic decline as an opportunity to focus on “high-quality population development”.

Overall, there are three major themes in Xi’s policy plan to meet China’s demographic challenge:

Developing the “quality” of the existing population. Investing in people, including improving health and education services.

Making China more family friendly. This includes better childcare and maternity leave, as well as building a family-friendly culture and combatting customs like expensive dowries that might discourage marriage.

Seizing the “opportunities” of population decline and responding to the ageing population. Making sure that older people lead good lives and growing the ‘silver economy’. Adapting new infrastructure to the new population, and taking the chance to protect and restore the natural environment.

The Chinese President’s article comes off the back of a new directive (here in Chinese), released by China’s State Council in October, that also aims to promote a “fertility-friendly society”, with a list of policies including better maternity leave, better medical maternity care, and more housing support for families (an English language report about the directive can be found here). It is not clear when or how these policies will be implemented or when ordinary Chinese people might begin to benefit from them.

Other parts of Xi’s article also reflect what has been trailed by the Chinese state earlier this year, including the encouragement to businesses to grow the ‘silver economy’ and turn the ballooning population of elderly people into an economic asset. Already, goods and services for older people account for 6% of China’s GDP.

The outlook

In populations where the number of people of reproductive age and the number of people below reproductive age has declined, stopping population decline is extremely difficult because even if those young people rapidly increase their fertility, there are not enough of them to avert decline as the attrition from older age groups continues. This is called negative population momentum.

In exerting this downward pressure on births and creating smaller younger generations, the legacy of China’s one-child policy has been to create a both smaller target and a more significant challenge for Chinese policymakers who want to see more people in China have children.

Consider that between 1960 and 2023, China saw its population of over 65s increase by 684%, and its population of under 14s decrease by 11%. By contrast, in the US, the population of over 65s increased by 276% and the population of under 14s increased by 7%.

The pro-parent policies that Xi’s article and the State Council’s directive outlines are positive, aimed squarely at making having and raising children in China easier. But if China is serious about mitigating population decline, the speed and extent to which they are actually delivered matters hugely, and the cultural and economic headwinds they pull against are significant.

Phoebe – with thanks to foreign policy expert Sam Hogg, whose Substack can be found here, and whose thoughts were very useful in writing this piece.

Hı, it might be late since i discovered this page now. One thing to consider about China's "recent" low-fertility is that it kind of shows that it's (together with other things) tied to finansical-security of couples. pre-2016 fertility of China is shown to us as around 1.8 and increasing (it might be wrong but it's the data what we have), which is pretty impressive if we consider that China is rapidly urbanised/industrialised country which do have negative effects on fertility (as we saw with SK), but after 2016, as Trump's election created finansical-uncertainty, it starts to collapse. We can also consider post-2016 "economic status" problem as one of the reasons for it too, since issues like youth-unemployment is tied to current internal problems in China. This issue could be useful when analysing Chinese TFR.