Falling fertility in Finland

What's going on?

“But childlessness is also rising among those who are in a relationship. Many couples are waiting too long. “People call me a lot in Finland. [They say] ‘I’m 42, my partner has had three miscarriages and she says she will not continue. And I understand I will never be a father. I’m the only child of my parents, and there’s nobody left, and help me.’” – Anna Rotkirch

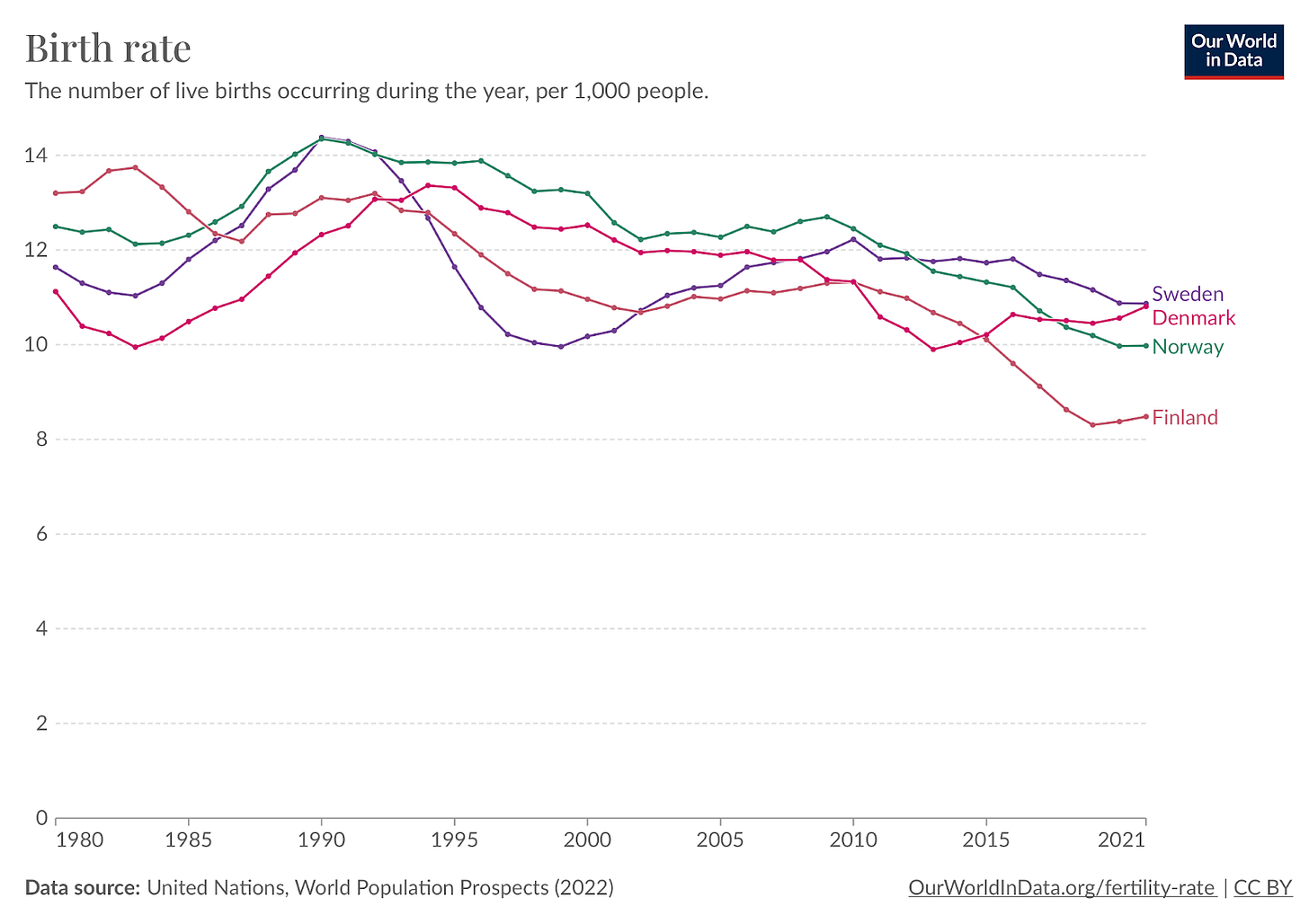

A recent FT piece caused a stir by highlighting that fertility in Finland has declined by nearly a third since 2010. In it, Henry Mance interviews Anna Rotkirch, research director at the Family Federation of Finland’s Population Research Institute. Rotkirch blames “something cultural, psychological, biological, cognitive” for the decline, adding “nobody really knows what’s going on.” It is perhaps this sense of the unknown that made the piece so alarming to so many.

Here we look at a number of studies, particularly Jalovaara et al. (2021), to better understand what factors might explain this trend. We should note that many of the papers we cite are the work of Marika Jalovaara, a Professor of Sociology at Turku University in Finland who specialises in demography.

Chance of lifetime childlessness varies – to a remarkable extent – by education level in Finland

Across all Nordic countries, the group in society likeliest to be childless are low educated men. Thirty-five per cent of low educated Finnish men born in the early 1970s were childless by the age of 45, and 31% of medium educated Finnish men. But only a fifth of highly educated Finnish men were childless by the age of 45.

Among Finnish women, the low educated group are also the most likely to be childless by the age of 45 but the variation is less extreme than that observed between men. However, we can see below that while highly educated Finnish women’s chance of childlessness have been fairly stable for decades, lower educated groups have seen their chance of childlessness markedly increase over the same period.

Low and medium educated Finns who do have children have more of them, probably because of unstable relationships

Low and medium educated Finns who do have children are more likely than highly educated Finns to have more of them, though two children remains the most common number across all education groups. While the number of low and medium educated Finns with only one or two children has declined, the number with more than two has risen, particularly the number of those with more than four. Highly educated Finns have not seen this change, with no decline in their likelihood of having only two children.

Jalovaara et al. (2021) attribute this effect to family instability. Looking at the 2003-2009 birth cohort, a paper by Jalovaara and Andersson (2018) found that the children of low educated Finnish mothers were significantly more likely than the children of high educated Finnish mothers to be born to a single mother (27% versus 7%). Sixty-nine percent of children born to highly educated Finnish mothers were born into marriage, while only 31% of children born to low educated Finnish mothers were. As Jalovaara and Andersson explain, this is important:

“...of all children born in a union, 41% had seen their original marriage dissolved by age fifteen. In addition, marriage does matter: among children born in marriage this proportion was one-third, while for those born to cohabiting parents, it was more than half. However, the disparities by maternal education are much more remarkable; this holds true especially at young child ages. For children of low-educated mothers, the likelihood of experiencing parental family dissolution is remarkably high: 43% of children of low-educated mothers had experienced family dissolution already by 6 years of age, and by age fifteen, the portion was as high as two-thirds. This finding can be compared to the same statistics of only 12 and 29%, respectively, among children of highly educated mothers. The relative differences by educational status are similar regardless of whether the child was born in cohabitation or marriage.” – Jalovaara and Andersson (2018)

Elsewhere, Jalovaara and others point to the relationship instability experienced by low to medium educated Finnish mothers to explain their increasing likelihood of having more than two children.

“Among low-educated mothers born in 1975–1978, nearly a third of the second children are with a different partner than the firstborn. In the case of the third child, the figure is exactly half, and 59% for the fourth and subsequent children. Among their medium-educated peers, the respective numbers are also relatively high: of the second children 14%, 30% of the third and 39% of fourth and subsequent children are with a new partner.” – Jalovaara and Miettinen (2022)

Overall, Finns who have never partnered have an increased risk of lifetime childlessness

“Childlessness seldom results from a single decision at a young age but more often follows from successive decisions or constraints that lead to a continued postponement of parenthood…” – Jalovaara and Fasang (2017)

Looking at Finnish men and women born from 1969 to 1970, Jalovaara and Fasang (2017) found that 45% of people were those who had never partnered (never cohabited with a partner) were childless, as opposed to 11% of those who were married, 19% of those who had cohabited, and 25% of those who had cohabited briefly.

In addition to being at a higher risk of partnership instability, less educated Finnish men and women are also more likely to never partner, raising their chance of lifetime childlessness, as found by Jalovaara and Fasang (2015). While more than a third of university educated Finns had married their first cohabiting partner and were still in that marriage by the age of 39 in 2012, only 13% of low educated Finns had followed that same trajectory.

Financial stability and economic certainty

Jalovaara and Miettinen suggest low educated Finns’ increased chance of never partnering could in part be caused by the diminished employment opportunities available to them, with financial instability making marriage or long-term partnerships less accessible or appealing.

Indeed, Hellstrand (2024), a paper which looks at economic uncertainty and fertility in Finland, found that greater fertility decline had been experienced by those working in fields characterised by higher levels of unemployment, lower income, and a lower rate of public sector employment, such as the arts and humanities, rather than those working in fields like health and education.

What lessons can policymakers who want to make sure people are able to establish families draw from Finland? Perhaps to consider how they can be helped to access financial stability and a secure attachment to the labour market.

Phoebe Arslanagic-Little & Anvar Sarygulov