High fertility on the Faroe Islands

Missing women & foreign brides

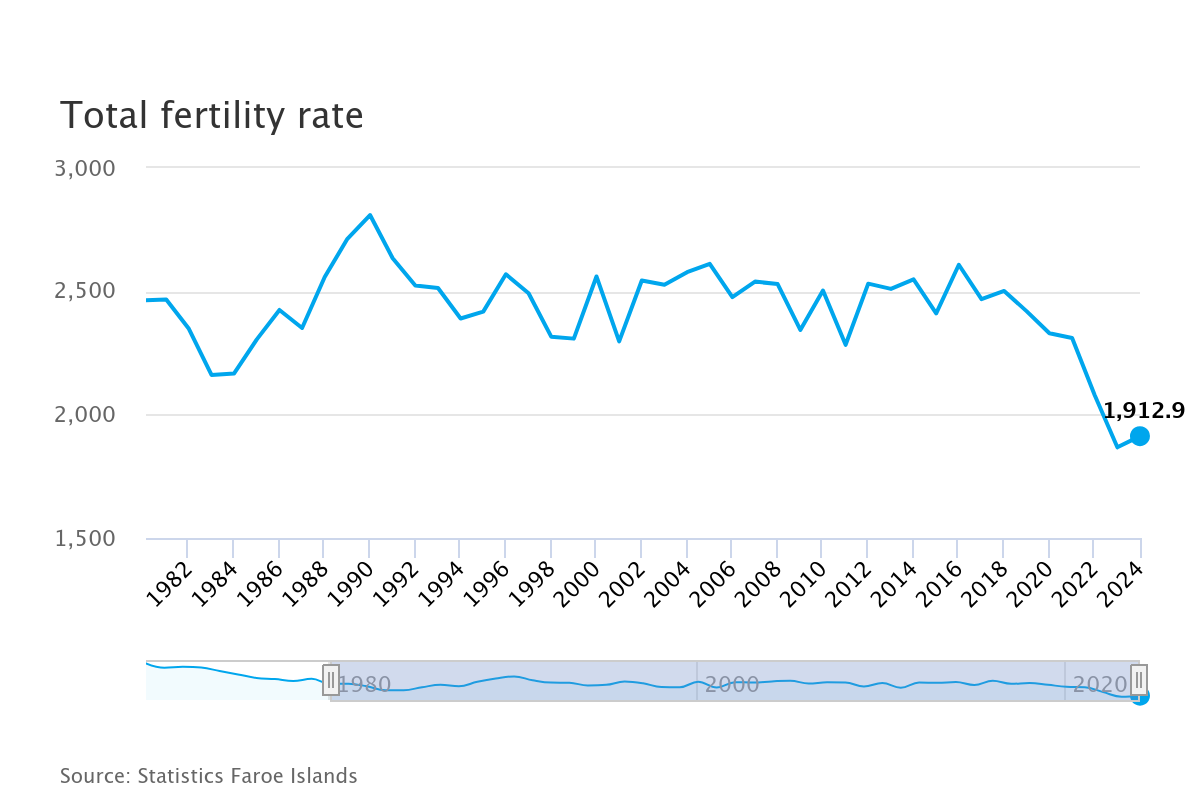

The Faroe Islands have considerably more people than sheep and one of Europe’s most skewed sex ratios. But they also have exceptionally high fertility. For most of the 2000s, the Faroese TFR – number of children per woman – was 2.5 or above. As recently as 2016, the TFR was 2.64 and today the Faroe Islands still have the highest fertility in Europe, at 1.91.

The Faroes are prosperous, with family-friendly employers and high levels of family stability. But counterintuitively, the Faroes’ high female emigration rate and the selection pressures it exerts may be also playing a role in boosting their fertility.

About the Faroe Islands

Although ultimately part of Denmark, the Faroes are to a large extent self-governing, even making their own trade agreements. Unlike Denmark, they are not part of the EU.

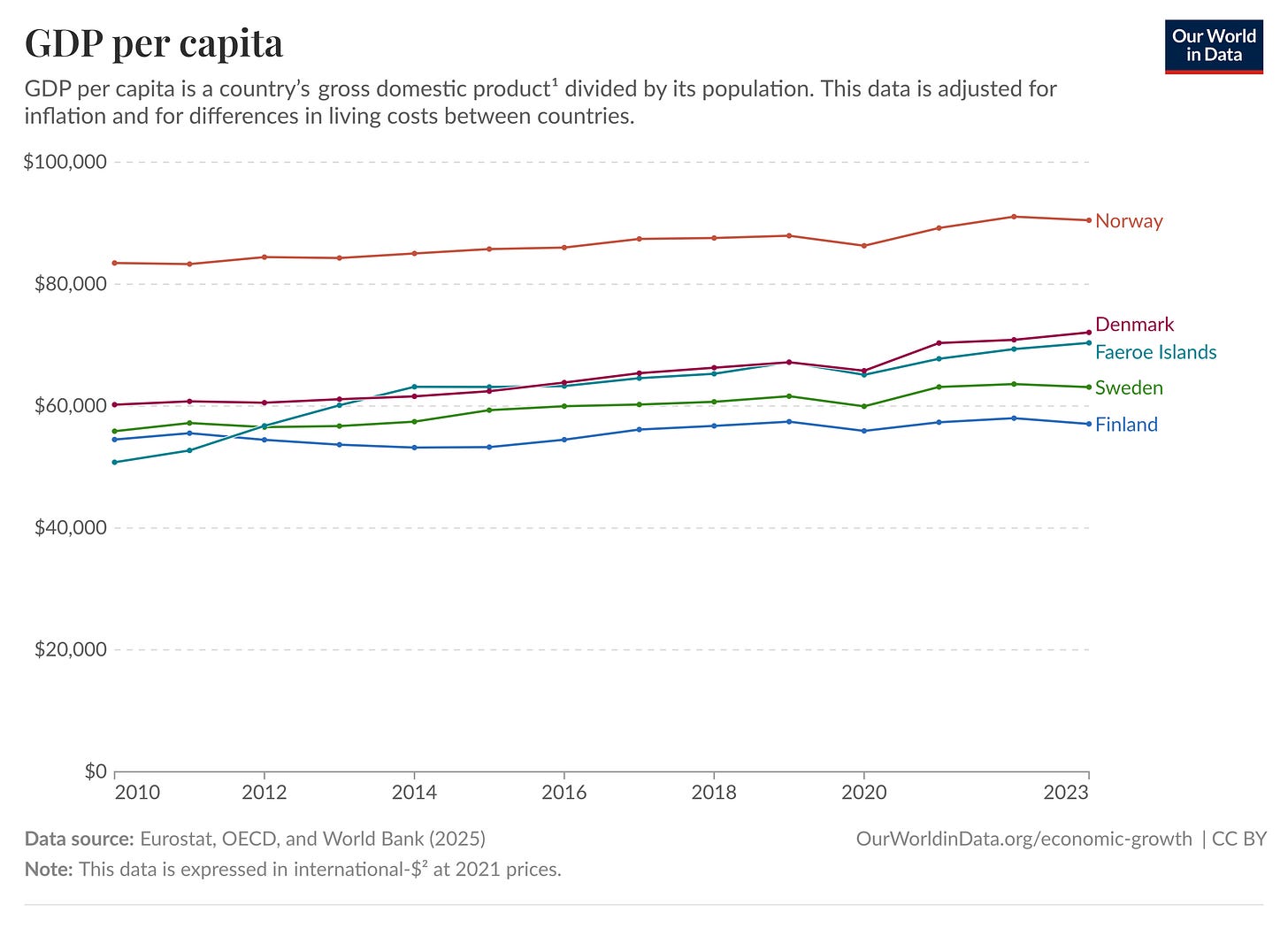

The population is just under 55,000 and is wealthy, with a GDP per capita that beats that of Sweden and Finland (not to mention the UK). The unemployment rate is very low at 1%. There is a small gender employment gap between men and women, 86.7% versus 83.2%, though very importantly, these figures include both part and full-time work (more than 50% of Faroese women work part-time). The Faroe Islands’ Gini Coefficient – a measure of income and wealth inequality, wherein 0 is perfect equality – is 22.6 in comparison with the UK’s 35.

Family breakdown is less common on the Faroes than in many other European countries. As of July 2025, out of 6,546 households with dependent children, 644 had only one adult, indicating that around 9.8% of households with dependent children are single-parent ones. In the UK, the share of households with a single parent is around 25%. The Faroe Islands’ divorce rate was 0.6 per 1000 people in 2024. It was 8.5 per 1000 people in England and Wales in 2023.

Family-friendly policies are in evidence across the islands. Childcare is very heavily subsidised. A nursery place for a child aged under two currently costs parents less than £15 a month for a three year old. For the first 14 weeks of maternity leave, an employee is generally paid her full salary by her employer. The following 44 weeks of leave may be divided between mother and father, and compensated to a maximum of around £3,500 a month by Barsilsskipanin, a state-run insurance scheme that exists to pay out parental benefits and aims to “to make it financially possible for children and parents to be together during the first period of the child's life"“.

Other commentators have emphasised the islands’ family-friendly culture and traditional family values in seeking to explain their exceptional fertility, but a key to part of the puzzle may lie in understanding why it is that so many Faroese women leave the islands and do not return.

Missing women and mail-order brides

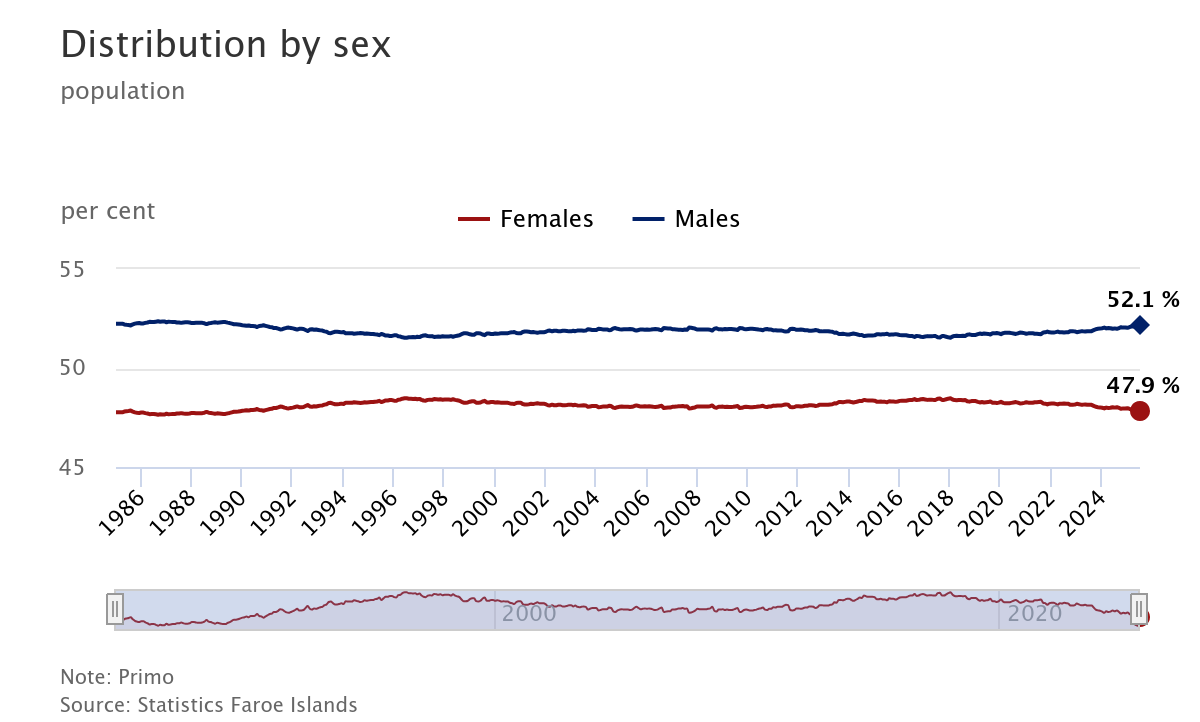

The Faroe Islands are one of the most gender imbalanced places in Europe. As of this year, 52.1% of the population is male and 47.9% is female. This is a worse sex ratio than China’s. As can be seen in the chart below, this is a long running problem for the Faroes.

The driver of this gender imbalance is emigration. Both young men and women leave the Islands for work, study, and for a different type of life, mainly for Denmark. But more women leave than men.

In 2024, a net sum of 275 women aged 15-29 emigrated from the islands. In the same year, a net figure 329 men of the same age group joined the population. This is probably in large part to do with the type of work available on the Faroes, with many people employed in male-dominated sectors including agriculture, fishing and manufacture.

For over a decade, some Faroese men have responded to the situation by seeking brides from other parts of the world, particularly from Thailand and the Philippines. One Thai woman, interviewed in 2017, told the BBC that she found adjusting to the long Faroese winter very difficult: "People told me to go outside because the sun was shining but I just said: 'No! Leave me alone, I'm very cold.'" Despite such difficulties and other culture shocks, as of July 2025, there are 801 women born in Asia resident on the Faroe Islands, many of whom report very much enjoying life on the islands.

Selection effects

The Faroes are surely reaping the benefits of their family-friendly culture and policies. Childcare is very affordable. Employers are accommodating of the needs of parents. Parents are likely to stay together, making it more likely that more children will be born. Certainly these are factors that make it easier to become and be a parent.

Also at play in the Faroes, tangled up as both a cause and an effect of its family-friendly policies, will be the effects of living in a community with lots of young families. The more people you know who have children, particularly peers, friends and siblings, the more likely you are to have a child yourself. The more familiar you are with young families, the more accommodating you will be of parents that you employ or who are your colleagues.

But there are very likely also selection effects acting to increase Faroese fertility. Faroese women who are keen to pursue a career will find that they can best do so off the islands. Many of these women choose to emigrate. That means that those women who choose to remain may be less career oriented and more interested in starting families and having more children. Added to this is the fact that many of the women who immigrate to the Faroes come expressly to partner and start families.

Conclusion

The Faroese fertility story may be about who chooses to stay as well as culture and policy. The islands retain, and to some extent attract, women who are more inclined to start families. That helps to create a feedback loop keeping fertility high, despite many women of childbearing age emigrating away.

«The Faroese fertility story may be about who chooses to stay as well as culture and policy.»

Culture seems to me to matter rather little: many countries with a "culture" of having many children switched to having almost no children in 20-30 years.

My guess is that women decide how many children to have and it is almost all about how much each cares about having a comfortable retirement and how profitable are sons as pension assets (secondarily about how sexually attractive are the potential fathers) and that in turn depends on how strong their reproductive instinct is and how cost-effective are alternative pension assets.

Every woman seems to evaluate the cost/benefits of having sons as a living pension versus having a career and a financial pension (private or from the state). It is not about education or affordability in themselves that drive the choice:

* Education as a rule is just a proxy for higher ability to have a financial pension instead of sons.

* Affordability means little by itself as in many countries natality rates have fallen with higher women incomes that is more affordability for spending on having children.

However at some point affordability does matter: when many women already have an entitlement to a financial pension and are affluent then having children is no longer a necessary expense to build pension assets but it can become an option and after all many women have some reproductive instinct, and whether they take the option depends on how expensive it is compared to other options like better holidays, a house renovations, a car upgrade, etc., as having children becomes an "experience", a "hobby".

Some time ago "The Economist" translated this into the language of economics and observed that in countries where women can count on financial pensions for their retirement children are no longer a necessary investment but an optional durable consumption good.

Very interesting! Do you have any idea why the TFR dropped off after 2020?