How South Korea's job market motivates intensive parenting

A new article in Works in Progress & some extra context

I have a new article about South Korea’s ultra-low birth rates, which is in the November print edition of Works in Progress and now also online. People often claim that because South Korea has failed to make it easier for people to have children, there’s no point in other countries attempting the same. In my article, I argue that the factors causing low birth rates in South Korea are so extremely severe that policymakers in other parts of the world must be careful not to over-extrapolate the South Korean experience onto themselves.

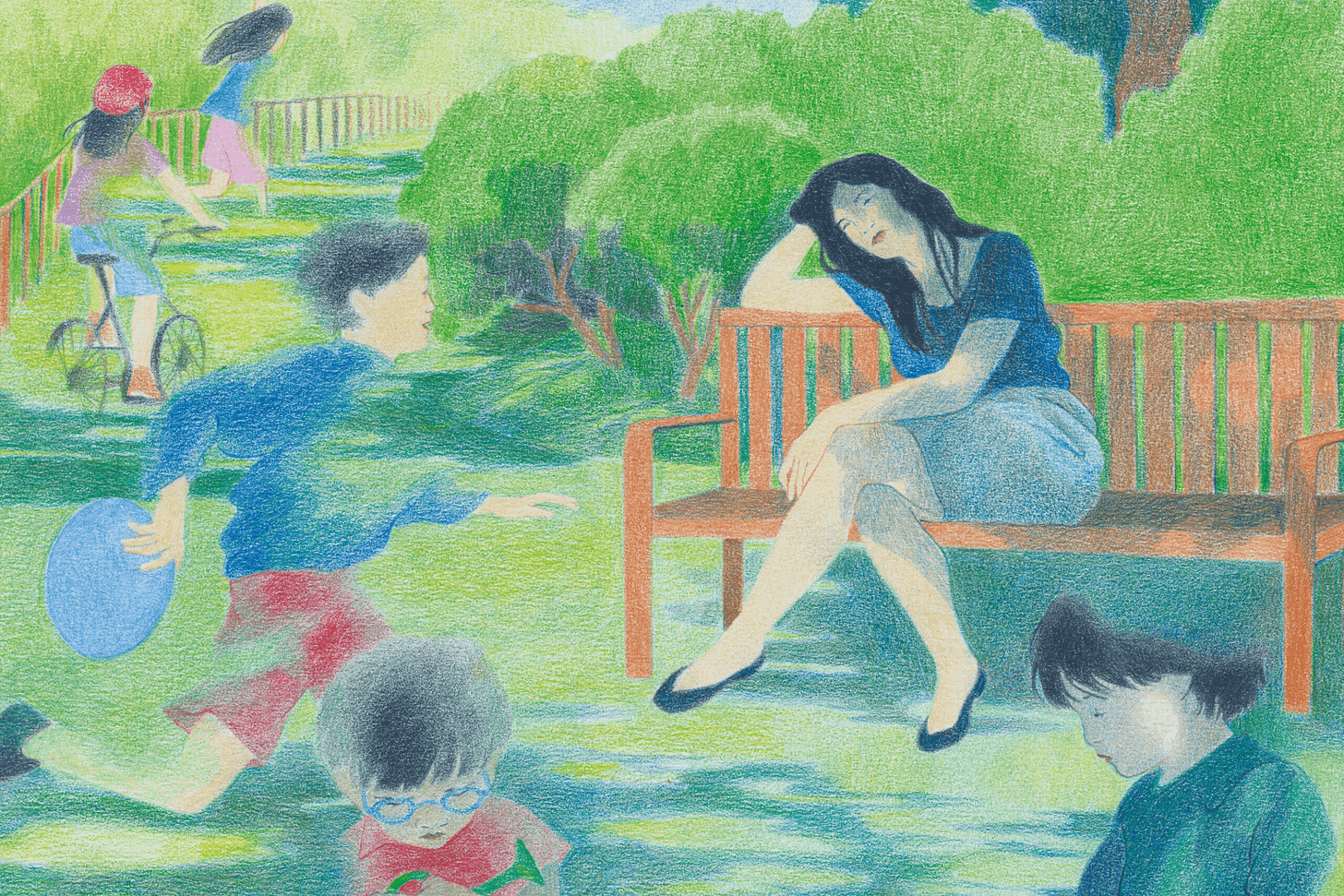

A major factor driving down births in South Korea is highly resource intensive parenting. A contextual factor that there wasn't the space to discuss in the Works in Progress article is how South Korean job market motivates this type of parenting, which is very demanding and unpleasant for both parents and children.

There is a tremendous productivity gap between South Korea’s larger and smaller companies – in 2010, it was found that small companies of 10 to 49 employees were just 22% as productive as those with over 200 employees. The productivity gap translates into a significant earnings gap of 50% or more between those employed at smaller and larger companies. Large companies, known as chaebol (think Hyundai and Samsung) are also more likely to provide a better environment for parents, including longer maternity leave. Most young South Koreans aspire to work for a chaebol.

South Korea’s labour market is not only extremely competitive but starkly divided between those who are employed in ‘regular’ versus ‘non-regular’ work, a phenomenon that the OECD describes as ‘labour market dualism’.

Non-regular workers include those: working part-time; in gig economy-style work; and temporarily employed on fixed-term contracts. Non-regular jobs are significantly more precarious than regular jobs, pay less well, and are less likely to provide workers with social insurance coverage. 27.3% of all those employed in South Korea are temporarily employed, the second highest share of temporary work in the OECD. As of 2021, 45% of employed South Korean women aged 15-29 and 39% of men aged 15-29 were employed in non-regular work. The lower pay associated with non-regular jobs might also explain the increase in the number of young South Koreans who have at least one extra job in addition to working full-time. The number of South Koreans aged 15-29 working at least one additional job increased by 30.9% between 2023 and 2024.

In a labour market with so many poorly paid and insecure jobs, and a very narrow stratum of significantly better paid and more secure ones, it is highly rational for South Korean parents to hothouse their children to the extent that they do.

I first learnt about these dynamics in this useful article on the Substack Chasing Sheep, which makes the interesting case that South Korea’s failure to embrace a market economy is a contributor to its low fertility. I strongly recommend you check it out if you want to know more.

Phoebe