Learning from large families

The 5% of US women who have 5 or more children

In an era of declining Western fertility, we think it’s vital to investigate and understand the factors that mean that people are having fewer children.

But what about the people who still have many children, even in countries where large families are nearing the status of historical curiosity? What drives these people, and what can we learn from them?

These are the questions that drive a new book – Hannah’s Children: the Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth – by academic Catherine Pakaluk. US women had 1.66 children on average in 2021, but Pakaluk sought out and interviewed the 5% of American women who have five or more.

The book consists of 55 interviews with these women (a sample of a larger number of interviews that Pakaluk and her research assistant carried out). All the interviewees are college-educated, and all are religious, including Jewish, Baptist and Mormon.

Phoebe has reviewed Hannah’s Children for a magazine called The Critic. Here are our three major takeaways from the book, including quotes from interviewees, and a note to explain why we think Pakaluk’s ultimate conclusion, that religion is the only solution to declining birth rates in the West, is incorrect.

#1 No helicopter parenting here.

“I couldn’t care less if my kids are happy. That’s their job.” – Laura, mother of 9.

Clearly, having and caring for a large family is demanding in lots of ways and Pakaluk’s interviewees are open about that: “My body’s falling apart now,” said Shaylee, mother of 7. But crucially, there is no trace of helicopter parenting in any of the interviews.

At Boom, we are concerned that social expectations of intensive parenting are unhelpful both for parents and prospective parents. That includes increasing expectations about the extent to which parents can control and influence their children’s feelings and experiences.

A 2019 study gave 3,600 American parents various scenarios involving children between 8 and 10, and asked them to rate if the ‘concerted cultivation’ approach (intensive parenting) approach or the ‘natural growth’ approach (non-intensive parenting) was better.

In one scenario, a child complains of boredom after school. In the concerted cultivation scenario, the parent responds by suggesting they sign the child up for a new activity, like music lessons. But in the natural growth scenario, the parent instead suggests the child go outside to play with friends.

Overall, drawing on all six scenarios, 75% of the participants – including college graduates and non-college graduates – rated concerted parenting approached as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’. Only 32% of college graduates and 38% of non-college graduates rated natural growth parenting approaches ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’.

Compare this with Laura’s quote at the top of this section: “I couldn’t care less if my kids are happy. That’s their job.”. Some people might even find Laura’s comment callous – but it is impossible to control if someone else is happy. There’s a lot we can do, as friends, parents, spouses, but we can’t reach into our loved ones’ brains and turn the toggle on their mood. Perhaps that’s easier to grasp when you have 9 children that you are responsible for loving, feeding and clothing.

In her review, Phoebe recalls witnessing an example of ‘gentle parenting’, a method which asks parents to refrain from giving children orders or punishing them, in favour of affirming their emotions:

“In a supermarket last year, I saw a small boy kicking his tired-looking mother, his tiny foot lashing out. “You are kicking mummy,” she droned serenely, “you are feeling angry. Would you like a cuddle to calm down?” How many children can one have if one believes this is the best approach, one, two? Certainly not nine.”

#2 Helpful siblings

“I love seeing them care for each other.” – Shaylee, mother of 7.

In the West, very large families are unusual. Phoebe once had a classmate who was one of at least 11 siblings – the family drove a minibus and lived in a former school. This was very interesting, and extremely out of the ordinary.

Because of the rarity of very large families, which we many of us only dimly recall stories of from our grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ days, there are dynamics of family life that have washed away from collective memory and experience. A key one is that in a large family, older brothers and sisters help their parents with their younger siblings in substantive and useful ways. That includes playing with younger children, counting them in the playground or putting the baby down for a nap.

“And so it’s funny because our culture wants to not have kids do [hard] stuff so that “they can have a childhood” but then when they don’t feel useful then they don’t know what to do. They feel depressed.” – Kim, mother of 12.

It may be strange for many of us to imagine a 10 year old being in charge of a baby. Yet this dynamic not only frees parents up, but Pakaluk’s interviewees were adamant that rather than spoiling the childhoods of their older children, these responsibilities were enriching, character-forming and enjoyable. Kim, mother of 12, said that feeling “useful” made her children happier and less likely to be depressed, and multiple mothers argued it taught their children positive behaviours, like sharing, early on.

In smaller families where children are close in age, this dynamic is much less likely to emerge or make sense. A few days after the birth of her brother, two-year old Phoebe politely but pointedly asked when it was that he’d be returned to the hospital.

#3 Parent joy

“...we’ve had such a track record so far with each kind being a new source of joy that it’s exciting to think it could happen again.” – Molly, mother of 5

Pakaluk’s interviewees all enjoy being parents. “This is life and joy in its purest form,” said Amanda, mother of 5. The interviewees all shone with parent joy, calling their children “blessings” and pointing out that as their families grew, so did the sheer amount of human delight generated by each baby’s arrival, because of the added joy of older siblings.

“We just fell in love with babies.” – Kim, mother of 12.

Despite all the interviewees being religious, the simple fact of taking great pleasure in their children as individuals was the major motivation behind their large families, not a sense of having children as fulfilling a religious obligation. Pakaluk also makes this point.

Why we don’t think religion is the answer.

This leads us on to Pakaluk’s conclusion. Pakaluk, a devout Catholic, ends Hannah’s Children by arguing that religion is the “only effective family policy”. The main thrust of Pakaluk’s point is that it is only faith that can make you value children over material goods and so lead you to have more of them.

It is correct that religiosity is associated with having more children. However, it is very unclear whether this effect is the product of faith itself or the strong communities that can accompany faith. If you attend a local church and are involved with its community life, as a parent, you may well receive extra support, including a pool of trusted people who you feel safe asking to watch your children for an evening.

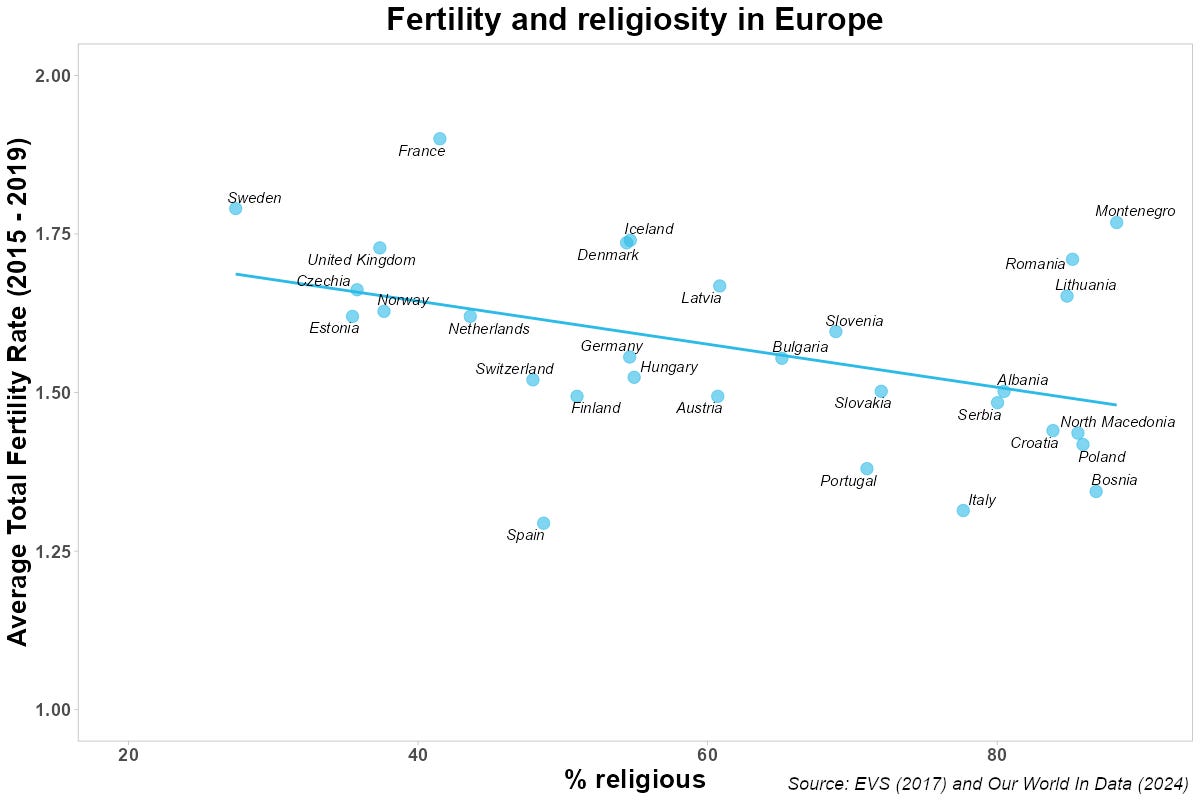

To muddy the waters further, consider that France, one of Europe’s most secular nations, was also its most fertile between 2015 and 2019. In contrast, in 2017, 78% of Italians described themselves as religious – Italy has one of Europe’s lowest fertility rates.

Again, Pakaluk’s very strong claim is that religion is the “only effective family policy”. That is not the lesson of South Tyrol, the Italian province we recently wrote about and that has been outpacing the national TFR for two decades. Nor is it the lesson of the Czech Republic, which we will write about soon. Only 36% of Czechs describe themselves as religious, but the government’s thoughtful and successful programme of pro-family policies has seen the fertility rate increase from 1.13 in 1999 to 1.83 in 2021.

Conclusion

Though we disagree strongly with Pakaluk’s closing argument, Hannah’s Children is a fascinating book. It’s not only very interesting to spend time with women who have chosen large families, but it’s clear that meeting the demographic challenge means being curious about the lives and decisions of people who have many children, as well as those who do not.

Phoebe Arslanagic-Little and Anvar Sarygulov