Sorry – immigration isn’t the solution

We need another answer to the demographic challenge

“The levels of migration needed to offset population ageing…are extremely large, and in all cases entail vastly more immigration than occurred in the past.” – Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Secretariat (2000)

Awareness of the UK’s falling fertility rate and the consequences of having fewer and fewer children on our economy and the public purse is growing. But at panel events, on podcasts, and in newspaper articles, there’s a point we see made again and again: “What about immigration? Surely that’s the answer to the economic effects of an ageing population?”. In this article, we explain why we don’t think that it is.

But first, how much immigration would we actually need to offset the effects of falling fertility?

Twenty-four years ago, the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs at the United Nations Secretariat published a paper that set out to investigate that very question for a number of countries, including the UK.

Published in 2000, the paper looks at the UK in 1995. In 1995, the UK had a potential support ratio of 4.1. The potential support ratio is the number of working-age people (aged 15-64) per one elderly person (aged over 65).

Without any immigration, the UN paper projected the UK’s potential support ratio declining to 2.36 by 2050. The paper also projected, for illustrative purposes, how much immigration would be necessary to maintain the UK’s 1995 potential support ratio of 4.1. Answer: 59.8 million net migrants between 1995 and 2050 – 1.087 million people a year – resulting in a population of 136 million of whom 59% would be post-1995 migrants or their descendants.

Since the UN paper was published twenty-four years ago, the UK’s fertility rate has continued to fall and migration levels have been less than the UN’s projected scenario. So far, our potential support ratio declined to 3.4 in 2021.

Similar modelling was published in 2023 by the demographer Paul Morland and the economist Phil Pilkington. They found that maintaining a ‘reasonable’ ratio of working-age people to those aged over 65 into the middle of this century – much less than the potential support ratio of 4.1 the UK had in 1995 and still lower than we have today – through immigration would require 37% of the UK population to be foreign-born by 2083, with annual net immigration starting at 500,000 and rising over time. Currently, just under 15% of the UK population is foreign-born.

What we take from both these papers is that the level of immigration necessary to protect the UK from the negative economic consequences of a shrinking working-age population would be very, very high, with levels significantly exceeding those of the last two decades (already a historic high).

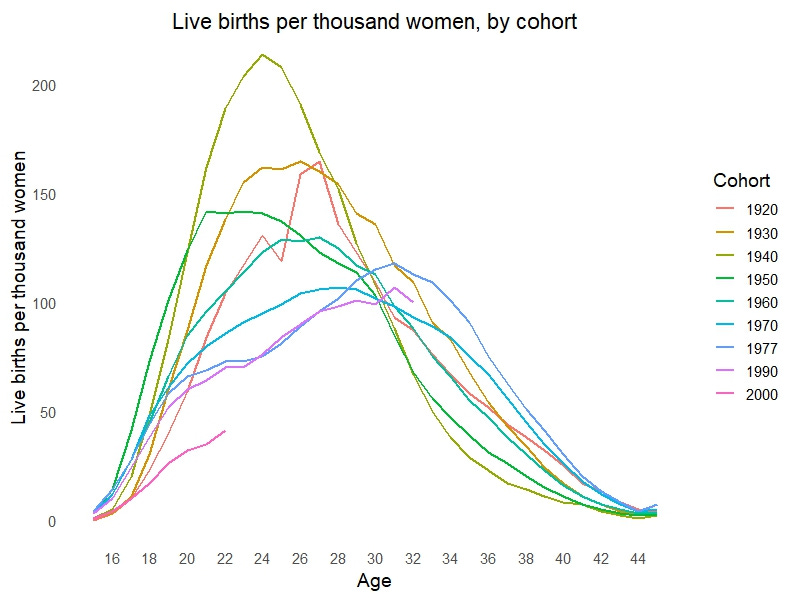

Crucially, the modelling in both of these papers assumes that the UK’s fertility rate will stay about the same. But if it in fact continues to decline – and there is consensus that it is likely to do so without policy intervention – the amount of immigration necessary to offset the population ageing effects will be even greater. Early data from the ONS suggests that Gen Z women are already significantly behind previous cohorts in terms of fertility.

Now that we have some insight into the level of immigration necessary to ‘solve’ the UK’s demographic challenge, here is why we don’t think it’s feasible.

Nations that have traditionally supplied much immigration to the UK – a good example is Poland – are also experiencing declining fertility and becoming wealthier too. In these nations, the economic pressure to migrate to countries like the UK is weakening, reducing the pool of people we can draw on.

At the same time, many other western countries are experiencing falling fertility and will be looking to bolster their working-age populations with immigration, meaning the competition for people will increase. Our competitors include the US, an extremely attractive destination for migrants. And as the knowledge-based economies of the developed world will require an increasingly skilled workforce, the competition for high-skilled migrants will be particularly fierce.

The effects of falling fertility and the competition for people mean that the UK might be forced to rely on low-skilled immigration from the shrinking pool of countries who have a high birth rate and low wages.

Currently, with net migration to the UK estimated to have been 672,000 in 2022-23, we don’t have a problem attracting people to join our workforce. But immigration at this level increasingly appears democratically unsustainable. Polling from 2023 found that 52% of British people think immigration should be reduced. Only 14% of Brits favoured an increase.

And very high levels of unskilled immigration of the kind we may be forced to rely on will struggle even more to find democratic support. In 2017, 42% of British people said that no unskilled labourers from India should be permitted to migrate to the UK, in comparison with 5% who said the same of professionals from India.

Democratic consent for immigration is important, regardless of one’s personal view on the issue. High levels of immigration without democratic consent risks unintended consequences. The continued success of increasingly radical and far right parties across Europe is driven in significant part by concerns around migration, and there is research that links levels of low-skilled migration in particular to increase in support for such parties.

Conclusion: immigration is important, but it isn’t everything.

Immigration is already very important in replenishing the UK’s working-age population and will continue to be. But we must also be clear that immigration alone cannot be the solution to the UK’s demographic challenge. We cannot count on being able to indefinitely attract the very high numbers of migrants necessary, and the democratic consent for permanent historically unprecedented levels of immigration as fertility declines is simply not there.

The claim that immigration is the solution to the demographic challenge is a distraction from the clear and urgent need to implement practical pro-family policies that can help more people to have children that they want, and we need to move past it.

By Phoebe Arslanagić-Little and Anvar Sarygulov

If taken to mean just allow income-maximizing (for residents) levels of immigration and there would be no problem from falling fertility rates, I agree 100%. There are many such things that should be done. But allowing income maximizing levels of immigration would still be a good thing, however much or little it addressed the demographic transition.

I'm a fan of more children (I subscribe here, of course, and have two) but I think the immigration modelling and description are overly pessimistic. I'm also an immigrant myself (from Canada to the UK), so am a bit biased, but I think the facts support me.

In the "migration, stagnation, and procreation" document, they describe a 14 percent first gen immigrant as being the highest experimented with, but Canada currently has 23 percent first generation immigrants as a proportion of the population and, other than a dramatic and unnecessary own goal on housing, is a peaceful society with high tolerance and a high standard of living.

The document also stresses the impact of immigration on inequality and stratification, which may be true for those first generation immigrants, but

1) They're dramatically better off than they would have been in their home countries, even if they're lower class in the recipient country, so the welfare argument doesn't work; and

2) That inequality often evens out by the second generation; loads of immigrants accept lower status work in the new country explicitly because they believe their children will live a better life, and are generally correct about that.

One more point the document fails to make is that we know how to create mass immigration societies and stagnation societies, but we have *no idea* how to create high (or even stable) fertility societies (which I accept is part of the job of this substack). I suspect policy will be part of it (housing being perhaps the biggest single factor), but I don't think it will be enough (albeit housing is a worthy goal on its own regardless).