South Korea's No-Kids Zones

"No kids please, we're Korean."

Imagine you are a South Korean parent. You want to take your 10 year old to a new café that has opened up a few streets away and treat them to a slice of cake. What’s the first thing you do? You go online, and check to see whether the café bans children.

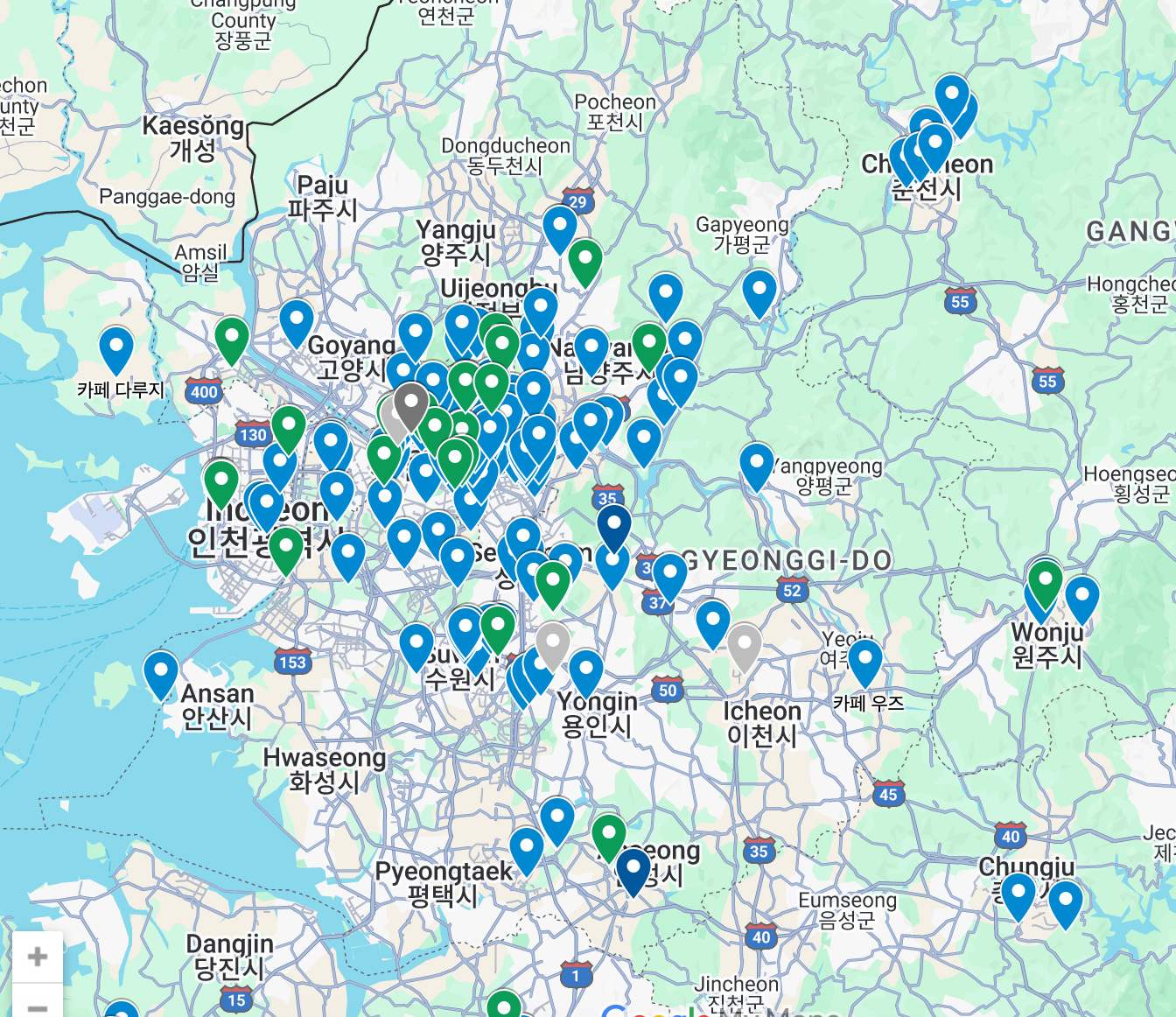

This map shows restaurants and cafés across South Korea that users have identified as officially designating themselves either as a ‘No-Kids Zone’ or as child-friendly in 2023. The 451 blue pins represent places where children are banned, and the 62 green pins are places where children are welcomed. Below you can see the cluster of blue pins in and around Seoul.

It’s difficult to know exactly how many South Korean establishments are child-free, but for cafés it was estimated at 5-10% in 2022, and has probably increased since then.

One area particularly dense in No-Kids Zones is Jeju Island, famed for its natural beauty, which has around 150 businesses that have banned children. A survey of Jeju’s No-Kids Zones reported that business owners had implemented the rule for reasons including a quiet atmosphere, problems with badly behaved children, and concern about legal liability in the event of a child accidentally getting hurt.

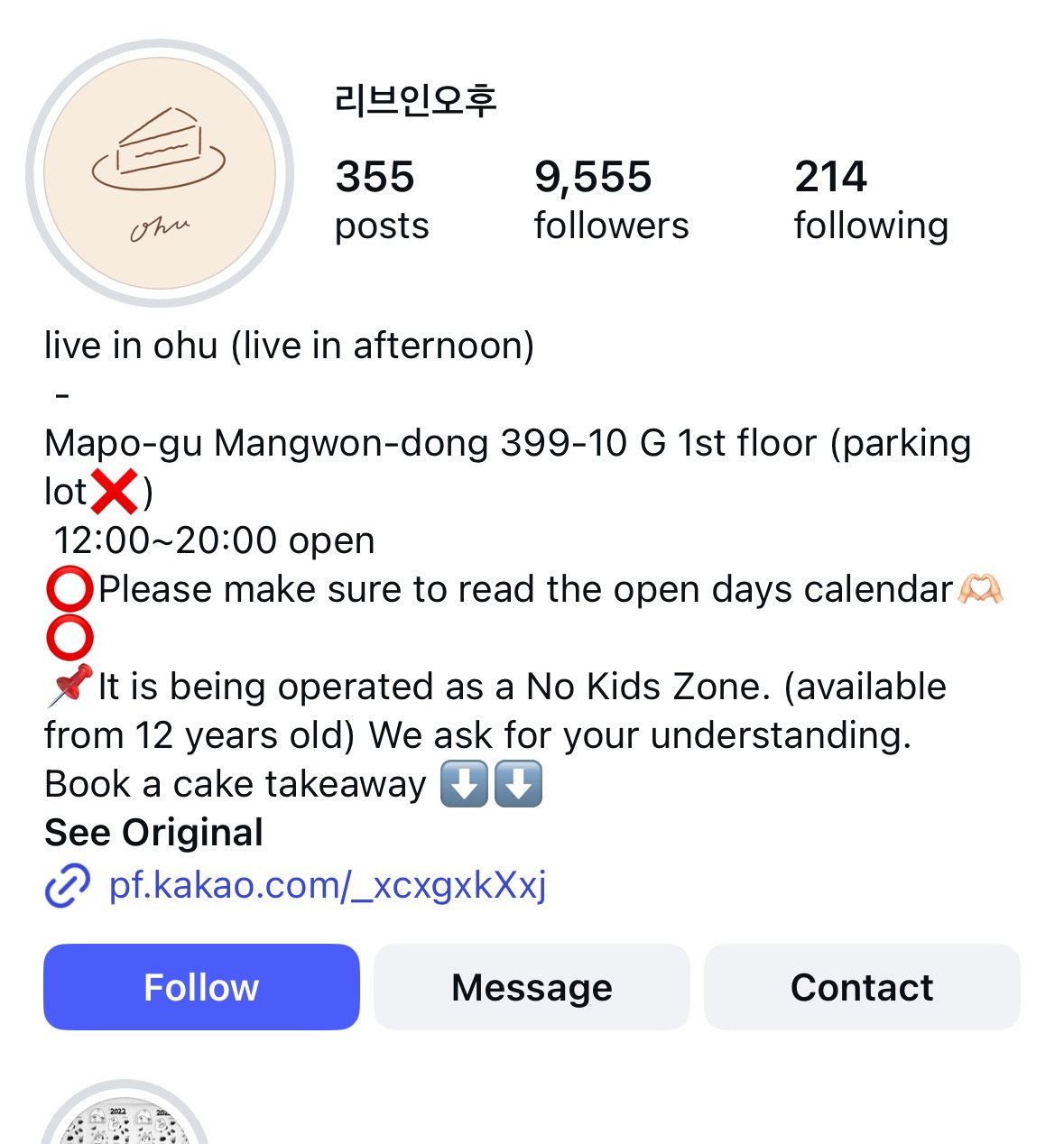

The below screenshot, from the Instagram account of a café serving what looks to be a variety of cheesecakes, is a typical example. It carefully specifies that no children below the age of 12 are allowed.

There is debate and disagreement over No-Kids Zones. In July, a Korean language post on X called out the above café in particular, and was retweeted well over 2,000 times. And the below post gives an insight into the tensions that surround No-Kids Zones:

When children stop counting

South Korea, the lowest birth rate country in the world, is facing depopulation. The government is spending significant sums of money on child subsidies in an attempt to make it easier for citizens to become parents.

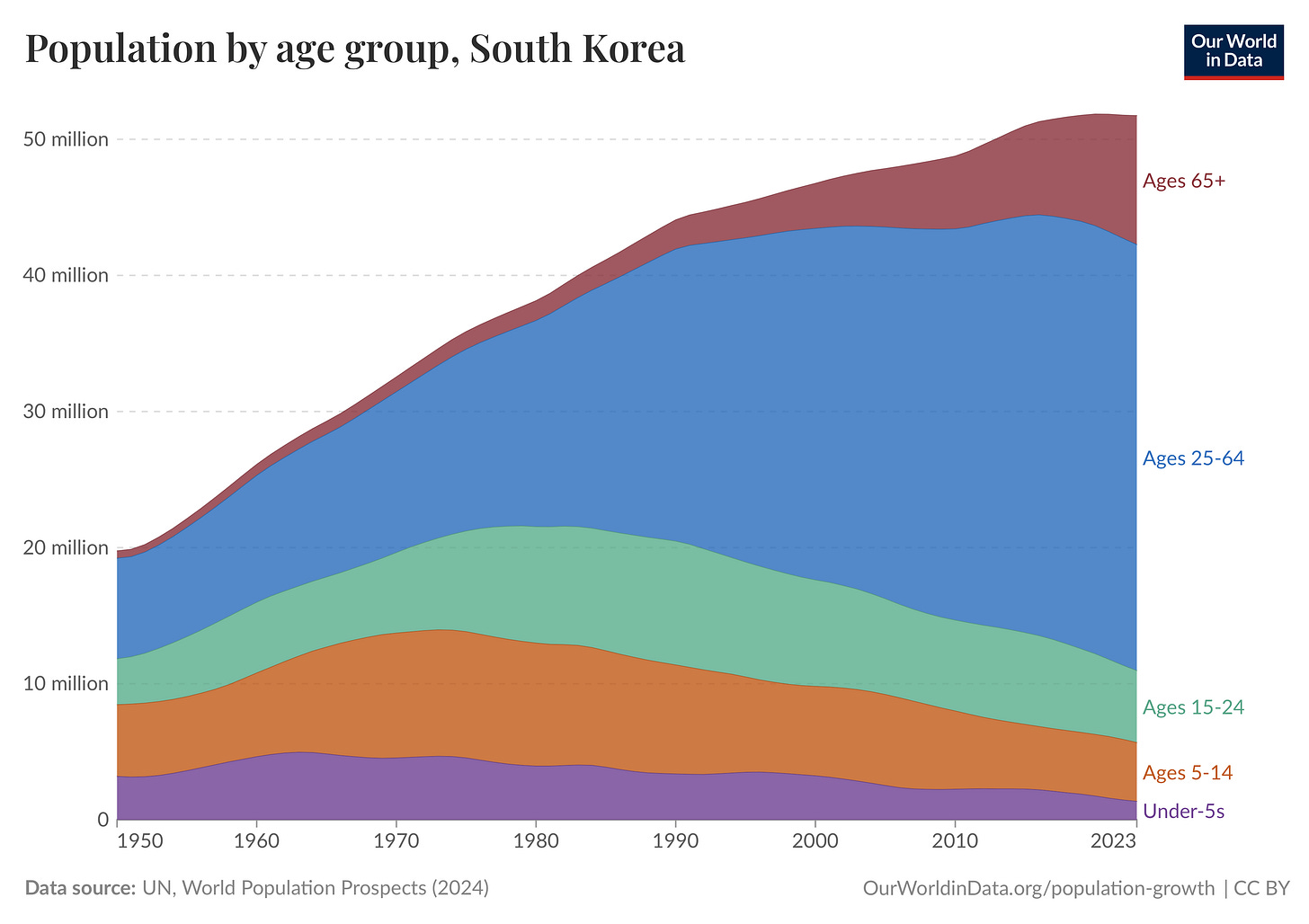

But in South Korea, as the above chart shows, children are a very small constituency. The share of the population that is aged under 14 is declining, and the share of those in middle age is increasing. Many of the people in that age group do not have children, aren’t sure if they want them, and may like the idea of eating cheesecake without any wailing toddlers nearby. For all the criticism that some businesses get online, 61.9% of South Koreans said they support No-Kids Zones in 2023.

No-Kids Zones should be understood as an outcome of South Korea’s ultra-low birth rates. They are a clear signal of the fact that the preferences of parents and children matter less as there are fewer and fewer of them, even as South Korean policymakers strain to make it easier to have children.

The consequences of No-Kids Zones

No-Kids Zones are probably now a minor contributing factor to South Korea’s low birth rates in two ways.

First, they mean that South Koreans are less likely to see young families in their daily lives. That risks making the prospect of having a family of one’s own feel remote. As we covered in The Baby Meme, there is a social aspect to fertility. By seeing other people’s children and understanding how parenthood fits into their lives, we are inspired to think about whether it might fit into ours.

Second, No Kids-Zones raise the cost of parenthood. A young South Korean man or woman is aware that there are many restaurants and cafés, perhaps places they currently enjoy, that they will rarely be able to go to for many years if they do indeed become parents.

Conclusion

To say that No-Kids Zones show that parents are being pushed to South Korea’s social periphery would be a significant over-exaggeration of the situation, and yet might be prescient. Certainly, No-Kids Zones are a manifestation of how ultra-low fertility is re-shaping South Korean urban life and norms. With fewer and fewer children, catering to the needs of younger families becomes less important, trumped by adult comfort. Another part of the challenge that faces South Korean policymakers.

I’ve heard it said that no kids zones are largely driven by liability. Apparently courts there are inclined to hand out excessive penalties when a child is injured at a business.

In which case, it’s yet another example of policy having unforeseen consequences. An effort to protect kids leads to families having fewer options and fewer kids being born.

But if 60%+ of the population supports them, maybe the noise of kids is part of it too. Or maybe liability got the ball rolling, but now it has taken on a life of its own where people seek these establishments out.

South Korea seems to be a culture that chose suicide.

They may not understand this right now, but the quoted 68% support for having no-kid zones means they decided to commit a nationwide prolonged suicide. This may be extended in time, and they will probably enjoy this time while it lasts, but at some point they will understand that they just will vanish off the face of the planet, and it will be too late to do anything. It is probably already too late.

Whoever wants to visit South Korea while it still exists - do it now.