The 'parent gap' between rich & poor

Richer people are more likely to become parents

With mounting evidence that wealthier people are increasingly more likely than poorer people to become parents in countries like the UK and US, access to family life is becoming a social inequality issue. Why, and what is the relationship between income and the chance of having children?

The complicated relationship between income and fertility

Do people inevitably have fewer children as they become wealthier? No, not necessarily.

Demographer Lyman Stone has recently written about how the relationship between income and fertility is not straightforward, but inconsistent both across cultures and across time: sometimes higher incomes are positively correlated with fertility, sometimes negatively.

For example, research published in July that looked at RCTs of interventions such as business training programmes in sub-Saharan Africa, found that women who became wealthier had significantly more children, not fewer.

There isn’t a straightforwardly negative relationship between income and fertility in European countries either, as new research is showing.

New research from the Netherlands

Dutch research published this month not only finds:

Dutch people on higher incomes are more likely than those at lower incomes to have children.

This positive relationship is strengthening for first births: income is becoming more important for the transition to parenthood, with an intensifying relationship between first births and income observed between 2008 and 2022.

The paper’s author, Dr Daniël van Wijk, found that while Dutch men in the top income quintile were 2.38 times more likely to become a parent than men in the lowest quintile in 2008, by 2022 they were 3.11 times more likely to do so.

The paper identifies a strengthening effect of income on chance of parenthood for women too. In 2008, Dutch women in the top income quintile were 1.63 times more likely to have a first child than women in the lowest quintile, but by 2022 they were 2.44 times more likely to do so.

Van Wijk also published a paper earlier this year looking at the relationship between income and first births – or chance of becoming a parent – in the US, Germany, UK, South Korea, Switzerland, Russia and Australia.

As shown above, van Wijk and his co-author identified that men and women in Australia, Germany, South Korea, the UK and the US are more likely to become parents as their income increases. They also found a positive relationship between income and first birth for Russian men, but not for Russian women, and the results for Swiss men and women were positive but not statistically significant.

Why is the gap between rich and poor widening?

This intensifying effect of income on chance of parenthood is likely being driven by declining fertility among lower income people. That means it is increasingly the case that earning a lower income makes you less likely to ever become a mum or dad. And the gap between richer and poorer in their ability to start a family is getting wider.

Resource intensive parenting (in terms of time and money) may be contributing to this gap. As our sense of what level of resource is necessary to raise a child increases, parenthood moves out of the reach of more and more people for longer.

Another major contributing factor will be increases in the non-negotiable costs faced by prospective parents – like housing. This means that economic pressures on young people in countries like the UK – including stagnant wages and the housing crisis – are driving postponement of parenthood to later and later ages.

Not only will these cohorts of young people not be able to start a family until later in life than previous generations, but when they are financially ready to do so, they may find that conceiving is difficult, particularly if they want a second or a third child.

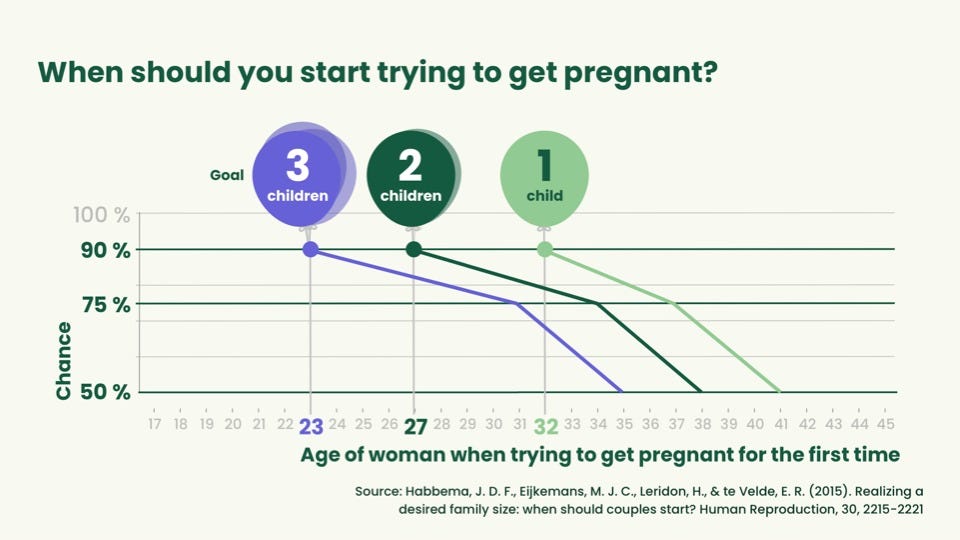

Consider the below chart, created by demographer Anna Rotkirch using a 2015 paper. A woman who wants a 90% chance of realising her ideal family size of three children should begin trying to get pregnant with her first child aged 23. For a 90% chance of having two children, she should begin at age 27, and for a 90% chance of having one, at the age of 32.

Closing the ‘parent gap’

The strengthening relationship between income and the transition to parenthood observed in countries like the US and UK should send an important message to policymakers. That message is that by increasing the financial stability of younger people, governments can help these younger cohorts start a family and counteract the trend of the postponement of parenthood to later and later ages.

New policy thinking is also necessary to better establish what government interventions can help young people in their transition to parenthood. It may be the case that policies such as more generous child benefit are particularly useful in helping people to expand their families, to have the second or third child that they want, but less useful in supporting those who are trying to ready themselves for parenthood.