Why is France different?

How policy has caused millions more French people to be born

Roughly fifteen years ago, there was a publishing micro-trend of self-help books that each centred around the supposed superiority of some facet of French culture. Good examples are the classic French Women Don’t Get Fat (about how much slimmer French women are) and French Children Don’t Throw Food (about how much better French parenting is). Well, here’s something that definitely is different about the French: they have more children.

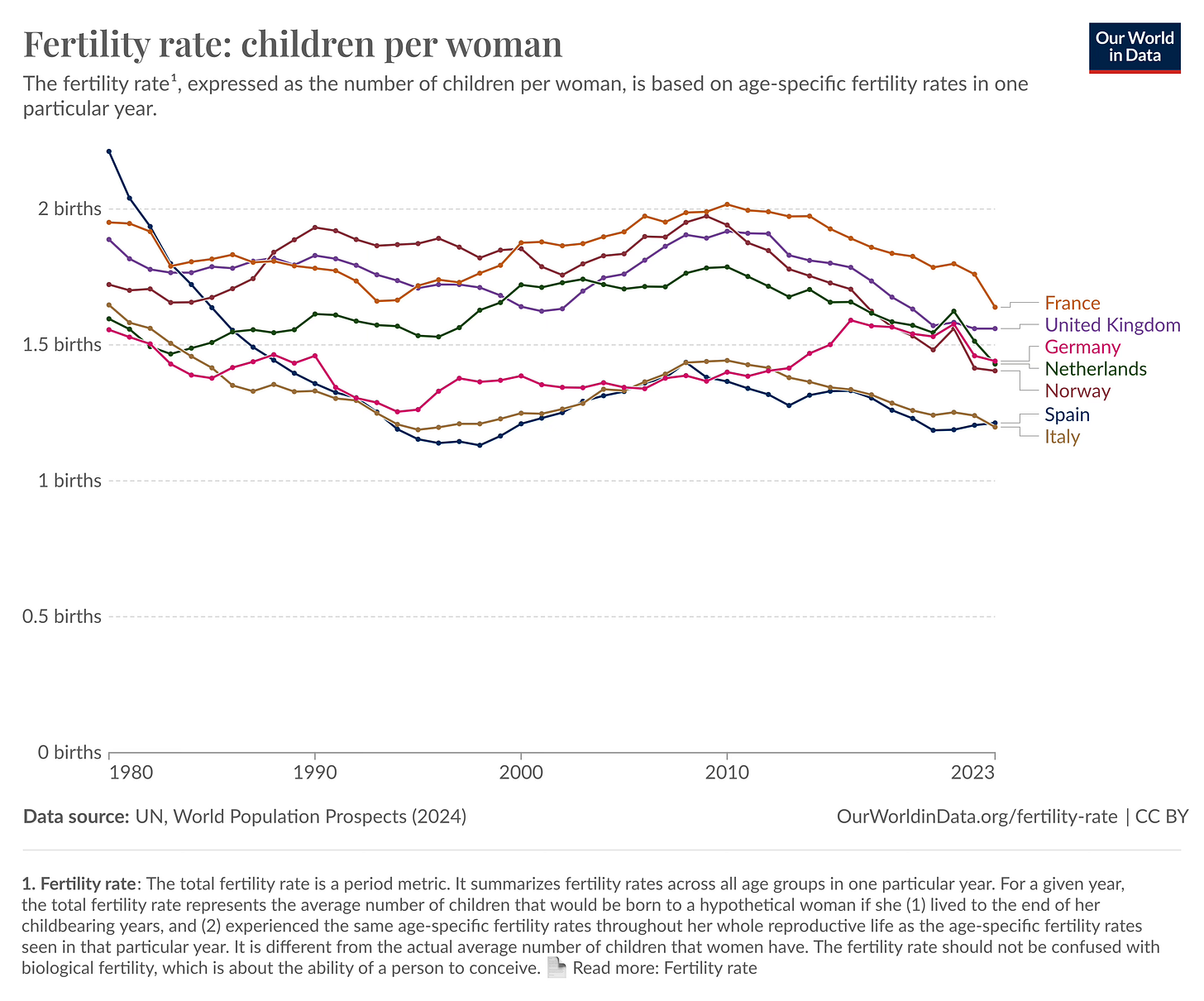

Today, French women have more children than those in any other European country, with a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 1.68, and a TFR that was at 2 from 2006 to 2014. To put this into perspective, 100 people consisting of 50 men and 50 women who partnered and had children, grandchildren and great grandchildren at the fertility rate of France today would expect to have 59 great grandchildren between them. But if those same 100 people instead had children, grandchildren and great grandchildren at the fertility rate of Spain (1.21 children per woman), they would instead have only 22 great grandchildren between them.

As outlined by demographer Lyman Stone in his informative 2024 report on southern European fertility, French fertility is even distinctly higher in comparison with the regions directly along its borders. This indicates that higher French fertility is not simply an effect of cultural factors. The French side of the Franco-Spanish border has higher fertility, and so does the French side of the Franco-Italian border. That is despite these being culturally similar regions with historically somewhat liquid borders.

My favourite example of this is Corsica and Sardinia. Both are islands, situated very close to one another, off the coast of Italy. Yet women in Corsica, which is French territory, have more children than women in Sardinia, which is Italian.

Have French people simply always had more children than those in other European countries? No. In fact for many decades, France was the Sick Man of Europe in demographic terms.

The French baby bust

“It grieves me to say it, but I see firm proof of the imminent disappearance of our country.” – Jacques Bertillon, French statistician, in Le Problème de la depopulation (1897).

The nineteenth century was one of declining birth rates across Europe, so that by the 1920s, more than half of Europeans lived in a country with a fertility rate below replacement rate of 2.1. But as outlined by economist Guillaume Blanc in Works in Progress, it was in France where birth rates fell first, a century earlier than anywhere else. I highly recommend you read Guillaume’s piece to discover the fascinating cultural drivers of this change.

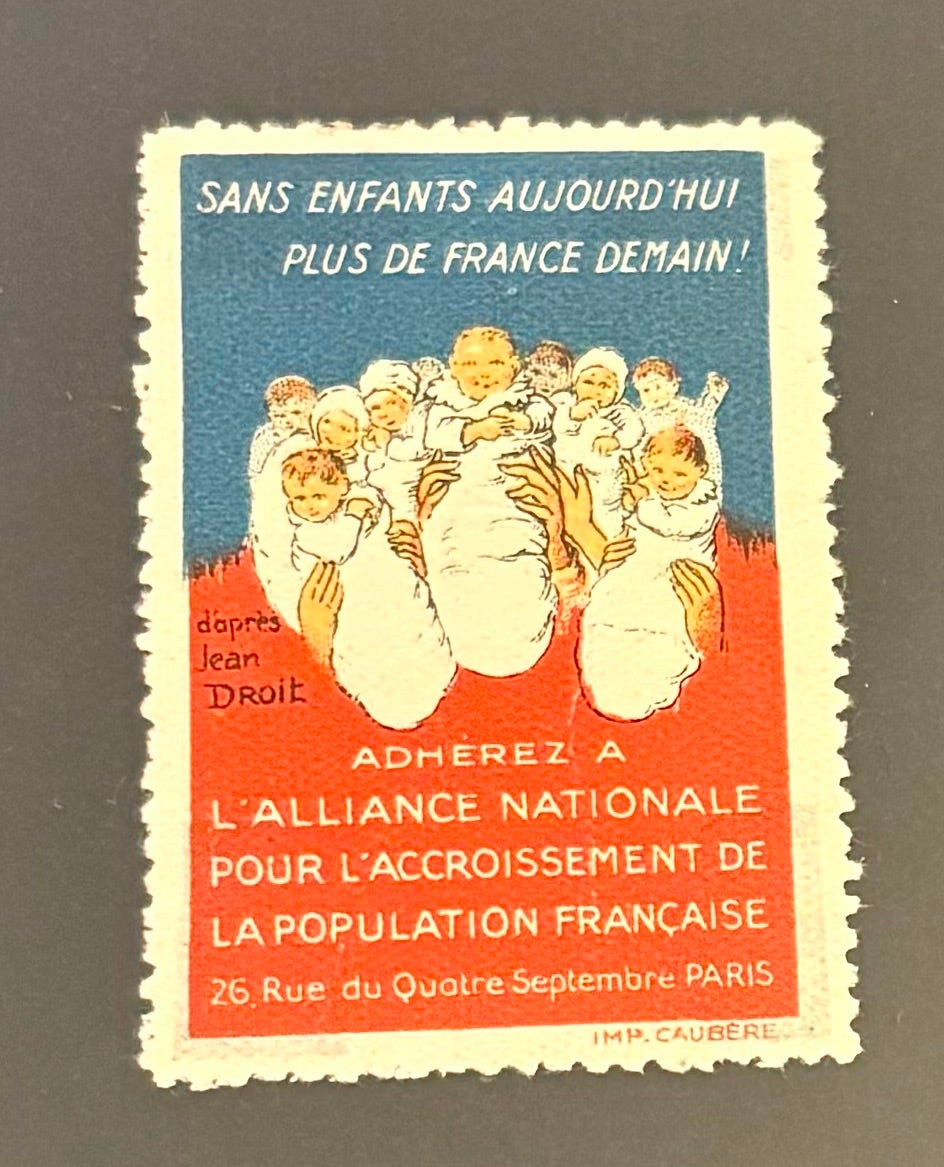

The French, including ordinary citizens, were greatly alarmed by their extended slump in births: a society called the Alliance nationale pour l’accroissement de la population française was created in 1896 to combat the scourge of depopulation and had 40,000 members by the 1920s, the largest of a number of such groups. After all, declining births was a matter of great geopolitical importance. France’s population had stagnated as that of its great rival Germany grew, leading to the production of posters showing two French soldiers being bayoneted by five German ones and explaining that for every five German soldiers born, only two French were.

What changed? How did France become Europe’s highest fertility country?

A century of pro-parent policies

French women today have more children than those in any other European country because of intentional, government policy that made starting and having a family easier. For over a hundred years, the French people have benefitted from a series of pro-parent policies, primarily via the tax and social security systems.

France’s family social security programme began in the 1920s but was greatly expanded post WW2 in a set of reforms akin to the UK’s Beveridge reforms. Today, France is the highest spender on family benefits in the OECD. These family-related social security policies are divisible into four main categories. First, benefits to support families following the birth of a child and in their early years. Second, maintenance benefits to help parents support dependent children. Third, payments for families in special circumstances. And fourth, housing benefits. Here is a list of these benefits by category:

Birth and early years benefits

Means-tested birth/adoption cash grant

Means-tested basic monthly allowance from birth until child is three years old

A child-rearing benefit to support parents who want to stop working or reduce their working hours to care for a child under the age of three

Childcare supplement for working parents with children aged under six

Maintenance benefits

Child benefit for those with two dependent children

Allowance for those with at least three dependent children

Means-tested income supplement for families with at least three children aged between three and 21 years old

Allowance paid to top up a low child support award, or for children who are not receiving any support from one parent (or both parents, in which case the allowance is paid to the person raising the child)

Special circumstances

Non-means tested education allowance for a disabled child

Means-tested back-to-school allowance

Daily allowance for any person looking after a child who requires constant care because of illness or disability

A means-tested cash grant to parents upon the death of their child, including in cases of still birth after the 20th week of pregnancy

Housing benefits

A house move bonus for those with at least three dependent children who move house before their youngest child is aged two.

Family housing benefit for renting couples who have been married for less than five years and have or are expecting a child.

Importantly, this family social security programme has always included universal benefits as well as means-tested ones, so that all French parents have felt the effect of at least some of these policies, regardless of income.

France also has a very family-friendly income tax system called the quotient familial, introduced in 1945, that uses ‘income-splitting’ to reduce tax bills for parents in line with how many children they have. Under the French system, a married couple with two children earning £50,000 pays £2,458 in income tax. Under the UK system, they would pay between £7,956 and £11,978 depending on how their income is split between them.1

As written by Lyman Stone in his paper, France’s pro-parent policies may have durably increased France’s fertility rate by as much as 0.3 children per woman, leading to millions more French people in existence today.

Conclusion

France offers a clear example of what can be achieved with pro-child policies that are administered consistently, over time. Yet it is also true that today France is again concerned about its falling birth rate, which has declined to 1.68 children per woman, incidentally the same low point that it dropped to in 1920.

Still, as recently as 2014, France’s birth rate was fairly steadily at 2 children per woman, very nearly replacement rate. But it slipped below 2 in 2015, the same year that the French government decided to cut or freeze some family benefits in order to save money. Even if France’s fertility decline since then is not attributable to that decision, and even if a fresh approach is necessary to see births in France rise again, the lesson of France remains the same: that policy can help more people to have more children.

Phoebe

Interesting stuff. What do you think about the 'reduced parenting intensity' argument for higher French birth rates? E.g. this Economist article claims that French parents spend less time with their children than in comparable countries, and that mothers actually spend less time parenting than they did 50 years ago, whereas in all other countries surveyed mothers and fathers spend much more than they used to. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/11/27/parents-now-spend-twice-as-much-time-with-their-children-as-50-years-ago

I've always been slightly skeptical of this data given how extreme the divergence is, and some of the individual country data (e.g. Denmark) seems very suspicious. But if it is true it would make sense that if parenting were less all consuming, it would lead to people having more children.